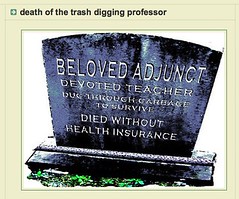

Ironically, this is not just a problem for students, but for too many higher education faculty who get in debt up to their eyeballs to get the degrees required to do their jobs only to find that they don't make enough to pay back those loans or at times even have income every month.

KEY EXCERPTS:Lenders of First Resort

More and more, student lending is becoming a rigged game.

By Robert VerBruggen

But there is a very important story in this book: Collinge, who is himself buried in defaulted debt, explores the alliances that student-loan companies have established with universities and the government. By sharing profits with schools in exchange for preferential treatment, the industry’s biggest players have shielded themselves from free-market competition; and through intense government lobbying, the industry has secured exemptions from laws that apply to other forms of lending. No matter how wrongheaded his analysis, Collinge’s facts should evoke cringes from Americans of all political stripes.

Schools’ relationships with the major lenders will come as a shock to many — especially those who’ve taken advice from purportedly neutral university employees. Through “school as lender” programs, lenders can essentially give schools a cut of the profits in return for financial-aid officials’ steering borrowers their way. (Technically, the school makes the loan, and then the lender buys the debt at a premium.) Lenders often sweeten the deal by offering officials lavish parties and trips. Sometimes, lenders have even run financial-aid call centers on universities’ behalf, with lenders’ employees claiming to represent the schools.

***

Today it’s a fully private entity, but Sallie and other big lenders have used their size and sway on Capitol Hill to their great benefit. For example, while there have long been limits on bankruptcy protection for student loans (some worry that it’s tempting to file for bankruptcy right after graduating), the student-loan industry managed to eliminate bankruptcy protection in 2005. No matter how long it’s been since you took out the loan, and no matter the size to which the debt has ballooned, you typically cannot discharge a student loan in bankruptcy. One can argue that bankruptcy laws in general should be stronger than they are, but it’s hard to make the case that student loans should be treated so differently from every other form of debt.

***

Many other foolish ideas have been adopted. According to federal law, a borrower can only consolidate his student loans once; then he’s stuck with that lender, even if a different lender is willing to pay off the loan and accept a lower interest rate. Also, to punish those who don’t pay their debts fast enough, collectors can have borrowers’ professional licenses taken away. Obviously, without being able to practice in the field for which they borrowed money to train, there’s little hope of these folks’ digging their way out of debt.

***

There are plenty of better ideas for rejiggering the way we pay for college. One is for students to give up a percentage of their income after graduation, instead of making traditional tuition and loan payments. Not only would this go easy on folks who have money troubles (no income, no payments due), it would take the burden off parents and the government. It would also provide schools with a very explicit way to compete on price: With loans, grants, and parental dollars out of the way, a student would have to ask himself if it was really worth X percent of his income to go with college A instead of college B...

***

FULL TEXT

To find out more & take action, go to Student Loan Justice.

|  |  |  |  |  |